The following is my entry in my Movies That Haven’t Aged Well Blogathon, being hosted at this blog from now through Aug. 31, 2015. Click on the above banner, and read a variety of blogs from movie viewers who have been disillusioned by revisiting movies they had previously enjoyed!

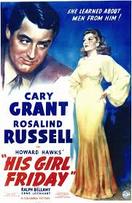

I first saw His Girl Friday 35 years ago in a college film class. Like most of my classmates, I was quickly enamored of director Howard Hawks’ lightning pacing, the overlapping, rapid-fire dialogue, and most of all, its brash heroine Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell). Here was a 1940 movie depicting a sassy, smart woman who worked as an ace newspaper reporter, the lone female in a pressroom filled with hard-bitten males who regarded her as their equal!

(For those not in the know, His Girl Friday is an adaptation of the hit play The Front Page, about Walter Burns, a fast-talking editor who conspires to keep his best reporter from leaving his job to get married. Hildy is about to leave when he gets the scoop of a lifetime — a man who is about to be railroaded and hanged for murder sneaks into the press office, and Hildy is forced to cover for him. In Hawks’ movie version, Hildy was gender-changed into Burns’ ex-wife.)

For years, I regarded this movie as a quietly feminist statement. A few years after I saw it, I myself married a female editor of a local newspaper. I showed her the movie, and she loved it, thereby cementing the movie in my memory as one of the all-time greats.

Recently, I signed up to participate in a blogathon devoted to strong movie heroines. Without thinking, I volunteered to write about Hildy Johnson for the blogathon. I figured I should refresh my memory, so I tried re-watching His Girl Friday. Unfortunately, it now seemed like a completely different movie.

As the movie opens, Hildy plans to leave town to marry her fiance, insurance salesman Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy, above far right). (I guess that should have been a tip-off right there. Whenever a scriptwriter wants to convey in shorthand that a character is a wimp, insurance salesmen and accountants are always the first go-to guys.)

The movie establishes that (a) Hildy and Bruce are leaving town that night to get married, and (b) Hildy has already quit her newspaper job and has been divorced from Walter for four months. Yet she makes a point of visiting Walter personally at his office to tell him of her impending marriage. That gives Walter a chance to try to sweet- and double-talk Hildy into coming back to work for him. When that doesn’t work, he worms his way into meeting Bruce, condescends gloweringly to the poor guy, and then takes the couple out to lunch so that he can work some machinations to make Hildy stay put whether she likes it or not.

Now, if Hildy knows what a finagler Walter is, why does she meet him face-to-face rather than telling him over the phone that she’s leaving? And why does she let Walter within ten feet of vulnerable Bruce, knowing how Walter can con anybody? The ostensible answer is that if Hildy didn’t do these things, we wouldn’t have a movie. But in the end, it makes her look either very needy or very stupid.

Sure enough, Walter manages over and over to get Bruce arrested or in trouble on some trumped-up charges just so that he can have Hildy working the story for him. We’re supposed to cheer Hildy on because she goes through hell and high water to get the story. And she does indeed have many triumphant moments. But let’s never forget: Those moments are all in the service of Walter Burns, the man from whom she tried so hard to untether herself in the first place.

(SPOILER PARAGRAPH ALERT!) In the movie’s finale, when Walter manages one last flim-flam on poor Bruce, Hildy — for the first time in the movie — breaks down and cries. But she’s not upset because Walter has again squelched her plans. She’s upset because Walter had just given her a big (and, as it turned out, fake) send-off speech, and Hildy was worried that Walter really didn’t want her in his life anymore. So, lucky Hildy, she’s in Walter’s clutches again — and Walter’s final lines of dialogue make it clear that Hildy is, indeed, his girl Friday.

I’ve never been fond of this one. It just seems so mean and not in a fun way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I adore Rosalind Russell, but I can’t get into this film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right that His Girl Friday, from title to ending, is wildly dated.

Now, I love the film, though Walter is a bully. To me, by placing a female in one of the Front Page roles, a feminist statement was made. But adding a romance plot added romantic comedy sexism. Hildy emerges as a talented woman who doesn’t know what she wants. In feminist terms, however, we can see her as a woman who is caught in the double-bind of the era: proper married women don’t work all hours chasing criminals for news stories, so Hildy, unlike Walter, has to make a choice that will necessarily leave half of her desires unfulfilled. Bruce is no good for her, as he doesn’t value her intellect (and has none of his own); Walter appreciates her smarts but uses her. There is no third option in the film as there might be in life: meet a smart man who isn’t a manipulative bully, find your lesbian side, or be alone until someone worthy of your awesomeness comes along.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very smart analysis! I had never thought of it in those terms. I guess these days, Hildy probably *would* have found her lesbian side and given Walter the heave-ho he so richly deserved. Thanks for commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoy these blog posts and blogathons so much because there are always multiple ways to interpret a film. I love to engage and analyze!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought that I was the only one that doesn’t like “His Girl Friday”. It’s good to know that there are others around that think the same as what I do. Nearly everyone I know votes this as their favorite film of all time, and because of that, I’ve tried watching it, and watching it again trying to see what all the fuss is about, but it just leaves me dull and I find myself getting bored. I even showed it to my Mum to get her opinion on it, and she didn’t like it either and found it boring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just came across this blog after rewatching His Girl Friday. I have to say, I completely disagree with your analysis. I think with respect to Walter’s character, you are confusing a strong and self-centered male lead character with an “anti-feminist.” Surely, a man can be selfish and yet think a woman is his equal. After all, he treats Hildy in the same manner he treats all of the men in the film. The entire film he cares about his own needs first, yet he trusts Hildy as one would an equal. Also, I think your analysis forgets that he really is her boss. Technically, at least in the workplace, they are not equals. But I don’t think this takes away from the feminism in the film.

In fact, I think it is the only truly feminist film of the time period that I have seen to date. First, you seem to take for granted that Hildy is an intelligent and sharp character. She chooses to go to Walter and give him the opportunity to foil her “plans” to marry Bruce. She purposefully wants him to engage in the manipulative double crossing that he engages in as a sort of last shot to get her back. Perhaps it is subconscious, but we truly see who is manipulating who at the very end when she breaks down in tears when she thinks Walter has truly given her up. All that aside, Walter consistently treats her as his equal. Perhaps knowing that she and he are very similar. Make no mistake, she is sharp and he knows it. He doesn’t talk down to her and supports her career. Maybe not in an altruistic way, because of course her success means the success of his newspaper. After all, he could have easily reassigned the important news story to any other male news reporter on his staff, especially considering the nature of the story at issue. For me, perhaps the most obvious note of feminism is seen at the end of the film where she is struggling carrying the large brief case for the type writer in her arms. Instead of taking the brief case from the “weak woman,” Walter simply tells her to carry it by the handle as it would be easier. He proceeds to walk out of the room before her without worrying that she can’t keep up with him, because he knows that she can and will keep up with him.

My favorite part of the film, which is rare if not unheard of in films of the age and even films today, is the fact that in the end, Hildy gets to “have it all.” She gets remarried with her equal, a handsome intelligent man who supports and understands her career. She loves him and he loves her. They aren’t a sweet couple in the traditional sense, but no one can deny they are “birds of a feather.” It is a romantic comedy, yet it is one where the woman does not have to sacrifice her passion for her career (which she allegedly plans to do with Bruce) in order to get her man.

I love this film and continue to see it as one of my favorite feminist films. I hope you will reconsider your opinion, as I think there is a lot in between the lines in this script.

Perhaps basing your opinion on what isn’t there rather than what is. For example, there is no doubt that Hildy doesn’t need Walter, as she is portrayed as a self sufficient woman who can survive without any man. The point is that she wants Walter, and in the end, she gets him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate your taking the time to leave such thought-through comments. And I realize that mine is a minority opinion. I just get tired of cat-and-mouse games in supposedly romantic comedies. It’s the same thing that eventually did in the TV series “Moonlighting”: After a while , you just want the couple in question to put up or shut up! (At least I did.)

LikeLike